Feminist performative practices of non-fascist living with AI and law

How does knitting, code, law, and women’s history of embodied and performative resistance come together? In this research project I explore relations between coding as women’s knitted secret coded messages in the resistance movements during World War II, and everyday resistance to contemporary forms of surveillance through knitted ”anti-surveillance” knitwear.

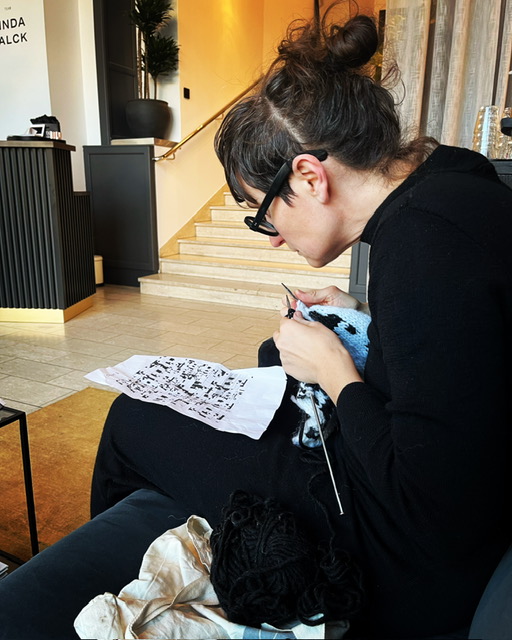

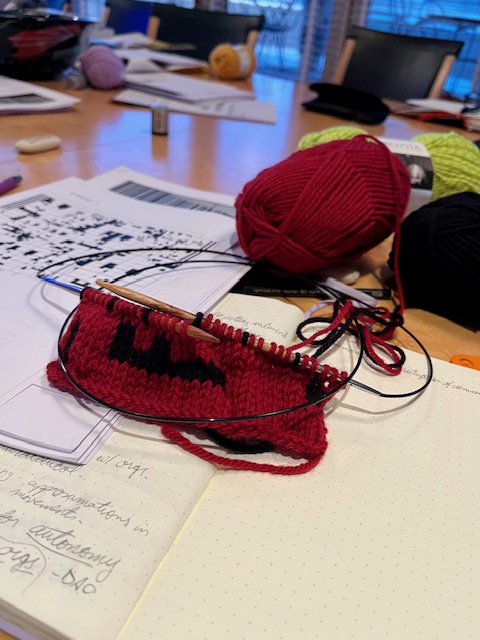

In a series of ”knit, code, resist”/”non-fascist living with AI and law” workshops – held in Gothenburg in 2022 (co-organized with Dr Rose Parfitt), in 2024 at the University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia (hosted by Dr Timothy Peters), and at La Trobe Law School, Melbourne, Australia (hosted by Dr Maria Elander), and at Newcastle Law School, UK, in 2025 – I have put knitting at the center, guiding workshop participants through a history of women’s knitting, of feminist theory and practice of knitting, code and embodied everyday resistance. All this while inviting workshop participants to knit, using yarns of different colors and qualities, and knitting needles provided for all (for non-knitters the balls of yarn have functioned as tactile ”de-stressing balls”). While interacting with the materials and with the provided knitting pattern (more on this below) as well as with each other – as participants’ pre-workshop knitting skills vary, and there is need to help each other out during the knitting – an intense focus and fluidity of inter-generational embodied practice, theory and method takes place as part of the workshop atmosphere.

Workshop participants often report on who taught them how to knit – often a grandmother – and that they have not knitted since at least their early teens. Others turn out to be highly skilled knitters. Few refuse to take the needles and yarns into their hands. While knitting the hierarchies that always govern academic workshop spaces are destabilized, as knitting skills are not distributed along the same lines as academic (formal) hierarchies: a distinguished professor may not be as skilled a knitter as the PhD student is.

The knitting invites workshop participants to consider what relations they have (had) through knitting and hand knitted garments – and what those relations mean to them. It brings out inter-generational care and kinship. As Lyda Maria Arantes argues, knitting is ”about the social and communicative context” in which knitting takes place (159).

The workshops set out to perform the continuous history of embodied and inter-generational feminist practice of resistance through knitting in the face of fascism and contemporary coding and use of AI. The process is one of ”thread-becoming-surface and the biography of the knitter interweave with and imbue each other in a continuous process of joint growth” (Arantes 154). The ”moving hands, the gripping fingers and the feeling skin – jointly holding and guiding needles and yarn – the inspecting eyes, the imagining, anticipating, calculating and directing mind, the thread uncoiling from the ball of wool; all join in the profess of creating.”(154).

Although seemingly very different and differently gender-coded practices – one (female coded) mundane, associated with women’s lives and the home/private sphere, and the other (male coded) with high-tech, hyper capitalism and speed – the similarities between coding and knitting are striking. In fact, knitting is a code based practice, building on ”mathematical (i.e. arithmetic) operations such as the rule of three in order to individually relate yarn (weight and quality), pattern, needle seize, desired texture and so on to each other and bring about a piece which correspond in seize, taste, and feel.” It is ”governed by sequences, numbers, and counting”. (156).

Knitting patterns provide elaborate coding charts with knit stitches, purl stitches and other stitches, the use of different colors, and a range of knitting techniques. Yet, in contrast to AI coding, knitting requires embodied practice-based skills. It also requires a lot of time. And, moreover, knitting patterns – how ever elaborate they may be – are quite useless if they are AI generated. ”Patterns are literally”, as Arantes points out, ”more than meets the eye and are enmeshed in a number of (mutually dependent) entanglements themselves: they materialise and visualise the knitter’s knowledge”. A knitting pattern, more than setting out the rules of engagement for the knitter, brings forth a vision (of what is often a bodily garment) transformed into mathematics and code, written instructions and suggestions of types of yarn and needle seizes, as well as images of the imagined end result.

There is always a balance between the presupposed knowledge of the knitter and how much the pattern explains: what does, e.g. ”Row 1: *p 2, k 2” mean? What is ”ribbing” – and does the pattern explain it? If the pattern instructs you to ”cast off 10 on spare yarn”, do you know what to do, and how to do it? Can it even be done (yes, it can but an AI would not know when, how and in which context casting off can be done).

In essence, AI is not an intelligence well suited for mastering the skill of creating knitting patterns that balances the coming together of bodily technologies of pressure, flow and resistance during knitting in relation to the human body and the material (the yarn and knitting needles) and their translation into actual knitted items.

Janelle Shane has created a number of AI-generated knitting patterns to test and explore what happens when you train an AI to create knitting patterns. She has invited experienced knitters to knit sample items of what the AI came up with.

Her AI-created knitting patterns project ”SkyKnit” shows that the result of asking an AI to create knitting patterns can be both playful and strange. Shane reports that ”Even debugged, the patterns were weird. Like, really, really nonhumanly weird.“ None of the patterns created resembles knitting patterns or knitted items that fulfill any purpose beyond play and imagination. And the knitters have reported back that the AI generated patterns were almost impossible to knit: mind boggling, but also inviting new ways of thinking-doing knit stitches or creatively interpret instructions to knit stitches suggested by the AI – stitches that does not (yet) exist and seems to be known only to the AI.

The finding to take away from the SkyKnit project is that the delicate technologies of the knitting human hand can only be translated into knitting patterns (code charts) by embodied experience of what a hand can do with which yarn and what knitting needles: How much weight of yarn can a hand hold – and for how long? What yarn quality will follow and collaborate beautifully with fingers prone to heavy sweating (which makes the yarn moist and produces excess resistance – hence the hand will get tired too quickly with a yarn that absorbs the sweat)? How does looping and cable knit feel to the knitter once what looks like a mathematically correct pattern (a knit code) translates into a knitted item through the bodily engagement of the knitter?

Micro fascism – Resisting

My ”knit, code, resist/non-fascist living with AI and law” project draws on posthuman feminism, Deleuze & Guattari’s theorization of micro-fascism, and Dan McQuillan’s work in Resisting AI – An Anti-Fascist Approach to Artificial Intelligence. It takes seriously, as Foucault puts it in the preface to Deleuze & Guattari’s Anti-Oidipus, that the challenge for our contemporary times is:

”not only historical fascism, the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini – which was able to mobilize and use the desire of the masses so effectively – but also the fascism that is in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us.” (Foucault, ‘Preface’, xiii)

Resistance to historical fascism – that of Hitler and Mussolini – was in part made in code: knitted code. As Nathan Chandler has discussed, there is a longstanding history of resistance and coding through knitting.

The perhaps most famous of wartime knitting intelligence is Phyllis Latour Doyle, a British World War II secret agent operating in collaboration with French Resistance in northern France. She was one of several World War II knitting agents using a combination of knit and purl stitches. She was able to pass as ”just a girl” who did nothing more interesting or dangerous than ”just unintelligent and uninteresting women’s stuff” – in other words: knitting. After having parachuted into Normandy, in 1944, she set out to befriend German soldiers, chatting with them, then knitting intel messages through specific combination of knit and purl stitches. The British secret service translated her knitted code into messages via Morse Code. While secret messages were often hidden in knitting baskets – where they could easily be found by the Germans, thus a risky method – the use of knit and purl as code was a coding method that the Germans never found out about or de-coded.

Another example is from the Belgian resistance: Recruiting women who had windows overlooking railway yards, the resistance received knitted code messages on the German train movements. The Belgian women coded the movements into their knits: Purl one for one type of train, drop one for another.

The transformation of mundane, everyday and embodied female-gendered technologies to core coding and resistance practices resonates with contemporary needs for employing a range of different technologies – regardless of their perceived gender-code or perceived ”intelligent” status to resist contemporary fascist tendencies and eruptions. There is great need to resist contemporary forms of fascism, and too little attention given to its forms, phases, processes and powers.

In looking at contemporary forms, spaces and practices of the fascism(s) ”in our heads and in our everyday behaviour”, McQuillan has convincingly argued that AI – including AI powered surveillance – is an important place to investigate. Its rapid spread and implementation in governance as well as in commercial space, the opacity of its operations, its carceral effects and decisionism, are some of the problems that McQuillan highlights as AI’s openness to fascistic desires.

In the ”knit, code, resist/non-fascist living with AI and law” project, and drawing on my collaboration with McQuillan and Daniela Gandorfer – in our forthcoming piece ”New Digital Technologies, Law, and a Non-Fascist Life? On Global Governance, Digital Networks, and the Molecular Unconscious” – I investigate both the micro-fascism(s) of AI and law, and the possibilities of feminist embodied resistance through knitting and other embodied feminist practices. If both AI and Law are easily captured by fascist desires, what can and must we do? How can we resist and lead non-fascist lives with law and AI?

Micro-fascism, as Guattari explains it, is not about seize or severity of fascism, but rather the level of articulation in the molecular and molar:

”We must abandon, once and for all , the quick and easy formula: ”Fascism will not make it again.” Fascism has already ”made it,” and it continues to ”make it.” It passes through the tightest mesh; it is in constant evolution, to the extent that it shares in a micro-political economy of desire which is itself inseparable from the evolution of the productive forces. Fascism seems to come from the outside, but it finds its energy right at the heart of everyone’s desire.” (171)

”Fascism, like desire , is scattered everywhere, in separate bits and pieces, within the whole social realm; it crystallizes in one place or another, depending on the relationships of force. It can be said of fascism that it it all-powerful and, at the same time, ridiculously weak. And whether it is the former or the latter depends on the capacity of collective arrangements, subject-groups, to connect the social libido, on every level, with the whole range of revolutionary machines of desire.” (171)

Resistance, rather than regulation (through law or otherwise), is thus an adequate response to fascism. As Dan, Daniela and I argue in ‘New Digital Technologies, Law, and a Non-Fascist Life? On Global Governance, Digital Networks, and the Molecular Unconscious‘, law is prone to become captured by the force of our fascistic desires. To work through a range of means of practices are necessary: knitting is one possibility of inter-generational, embodied and practice-based resistance.

While others have worked with public protests, organized resistance both inside and outside of democratic processes, my interests are in the everyday practices of resistance: those that are rarely noticed yet which takes seriously that it is only through us human individuals taking issue with our own individual fascistic desires that non-fascist living can become realized.

Feminist embodied resistance through everyday mundane practices: knit resistance to micro-fascism

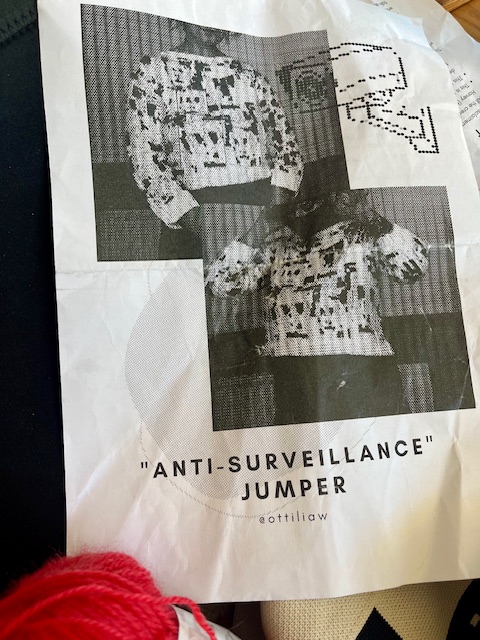

For the latter – feminist embodied resistance through everyday mundane practices – the project takes on and works with Ottilia Westerlund‘s knitting pattern ‘”Anti-surveillance jumper, a knit pattern that translate resistance to AI-powered everyday surveillance into knitwear. In doing so, it continues the history of women’s resistance to fascism through code-in-knitting during Wold War II. Westerlund does not make this reference herself in the knit pattern – the historical, political and social context is part of what my project and the ”Knit, code, resist/AI, law and non-fascist living” workshops brings to it.

Westerlund’s pattern is based on Adam Harvey’s hyperface project: a ”False-face computer vision camouflage patterns designed and developed for Hyphen Labs’ NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism at Sundance Film Festival 2017.” The hyperface and Westerlund’s pattern is designed based on a particular weakness in OpenCV’s default frontalface profile, and it is applicable to the Viola-Jones Haar Cascade algorithm. Rather than to try to disguise or hide the human face, the hyperface/Anti-surveillance jumper knit pattern ”aims to alter the surrounding area (ground)” rather than ”the facial area (figure)”. As Adam Harvey x Hyphen-Labs explain it:

”In camouflage, the objective is often to minimize the difference between figure and ground. HyperFace reduces the confidence score of the true face (figure) by redirecting more attention to the nearby false face regions (ground).

Conceptually, HyperFace recognizes that completely concealing a face to facial detection algorithms remains a technical and aesthetic challenge. Instead of seeking computer vision anonymity through minimizing the confidence score of a true face (i.e. CV Dazzle), HyperFace offers a higher confidence score for a nearby false face by exploiting a common algorithmic preference for the highest confidence facial region (i.e. use largest face). In other words, if a computer vision algorithm is expecting a face, exploit its expectations.

In technical terms, HyperFace is a computer vision camouflage that exploits the low-dimensionality of the low-resolution grayscale face image training dataset used to train haarcascade profiles. It works because the profiles were used universally. Breaking one profile meant breaking the profile everywhere because all CV systems relied on the same, vulnerable face detection profile. This is no longer true for DCNN-baesd face detection system.”

Thus, HyperFace and Westerlund’s knitting pattern respond to a relative weakness in the facial recognition software. It targets the difficulty in training an AI to recognizing and separate between context and target when the target – a human face – can look quite much alike a non-face environment.

Westerlund’s knit pattern is not an ”invisibility cloak”. Rather, it invites the knitter to creatively work with code and counter-code, with play and resistance, and with the possibility of using your body to perform your self – your identity and your data – in contestation to a particular kind of code intended for surveilling you. As she points out, the aim is not to disappear, but rather to think-by-doing of new ways of resisting being surveilled. And, I add: continuous ways of resisting fascism in our selves as well as where ever fascism takes place, conjures power and gains hold in this world.

My knitting practices

I have knitted Westerlund’s pattern in a few different variations: sample knits (an blanket project of knitting samples from around the world is in the making), a scarf, and a jumper (ongoing). The aim in knitting a variety of items is not to ”test” if the pattern actually responds to Haar Cascade algorithms or other facial recognition software. Rather, it is:

- knitting as non-fascist living, addressing the ”fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us.” (Foucault, ‘Preface’, xiii)

- knitting as inter-generational relations

- knitting as lateral thinking and knowledge

- knitting as feminist practice

- knitting as continuing women’s history of resisting fascism

- knitting (in public, in academic settings, as part of everyday life) as intervention and awareness raising of AI surveillance and modes resistance

- knitting as entangled and tactile becoming

- knitting as joyous living

ESIL, Vilnius, 4-6 September 2024: Technological Change and International Law

Attending a conference dedicated to the thinking through technologies and international law, I took the opportunity to knit through all sessions. I presented as part of the posthumanism and international law panel, chaired by Emily Jones, with co-panelist Gina Heathcote and Pierre Walckiers, a panel that raised questions of more-than-human relations to data, oceans, and plants, among many things.

To knit as a ”non-frontier”, ”non-intelligent”, ”non-fast” and ”old” technology served as a reminder of how ”technological change” (as the theme of the conference) not only means attending to what seems ”new” – as if technologies were new to international law, and international law had never dealt with technological changes before – but necessitates a deep understanding of how international law and technological change are co-constitutive of each other. Moreover, as we discussed in depth by the Technology, Vulnerability and Human Rights Law panel – chaired by Thomas Streinz, and with presentations by Daragh Murray,

Angelina Fisher and Victoria Guijarro Santos, when working with AI as an international legal scholar and lawyer, practices and platforms of both analysis and intervention by resistance are important. Anti-surveillance knitting is one of the modes of everyday resistance – counter coding and data hacking as a anti-surveillance action for human rights were discussed as other modes of resistance during the panel.

Knitting at the ESIL conference together with Roman Chuffart.

Read

Lydia Maria Arantes, ‘On knitted surfaces-in-the-making’, in Mike Anusas & Cristián Simonetti (eds) Surfaces: Transformations of Body, Materials and Earth. Routledge 2020, 152-166.

Dan McQuillan, Resisting AI – An Anti-Fascist Approach to Artificial Intelligence, Bristol University Press 2022.

Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, Anti-Oidipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Bloomsbury 2013 [1972].

Félix Guattari, ‘Everybody wants to be a fascist‘

Dan McQuillan, Matilda Arvidsson and Daniela Gandorfer, New Digital Technologies, Law, and a Non-Fascist Life? On Global Governance, Digital Networks, and the Molecular Unconscious. In: Fleur Johns; Gavin Sullivan and Dimitri Van Den Meerssche, eds. Global Governance by Data: Infrastructures of Algorithmic Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2025.

David N.G. McCallum, Glitching the Fabric: Strategies of New Media Art Applied to the Codes of Knitting and Weaving. University of Gothenburg , Dissertation (ArtMonitor Doctoral Dissertations and Licentiate Theses, the Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts, no 68)

Matilda Arvidsson. ‘The Regular Complex and the Advanced Complex: Écriture Feminine as Translation of a Life with Jurisprudence through Coding a Knitting Pattern and then Knitting It’, in N. Järvinen (ed.) Socio Legio Light: Liber Amicorum for Panu Minkkinen (2025): 99– 120.

On knitting as code, and knitting as coding see:

Genevieve Krzeminski, ‘A Binary Transformation from Knitting to Coding’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MK2cthrlQHg and related videos on code for knitters and knitting for coders/software as soft wear and soft wear as software.

Katie Cunningham, ‘Coding and Knitting’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JiXMdlw83oE

For more on World War II women’s knitting as code, see:

Helen Fry (2023) Women in Intelligence: The Hidden History of Two World Wars. Yale University Press.

Nathan Chandler ‘Crafty Wartime Spies Put Codes Right Into Their Knitting’: https://history.howstuffworks.com/world-war-ii/spies-codes-knitting.htm

Spies once used knitting to send coded messages—and so can you

Knitting as resistance, at the Law & Gender Conference, Copenhagen, August 2026

”Smash the patriarchy” jumper (2025), ”Feminist sisterhood” jumper (2025), and ”Do I bug you” jumper (2025). Knit design @MatildaArvidsson